BLACK excellence continues to be confined to the football pitch. That fact was underpinned by the recent sacking of Nottingham Forest head coach Nuno Espirito Santo. After 21 months in charge, securing European qualification, the Forest leader was ousted just three games into the season, writes Sam French.

In packed stadiums across the UK, Black players take centre stage every weekend- leading attacks, marshalling defences, and shaping outcomes.

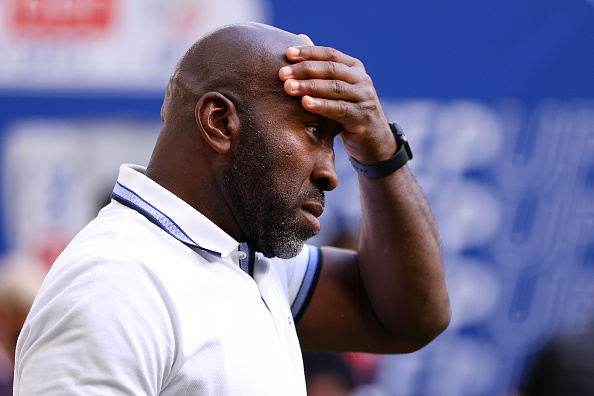

Nottingham Forest boss leading the charge of mid table clubs

Nearly 43% of Premier League footballers are Black. Social commentator and activist, Patrick Vernon MBE references their contributions, explaining that “if Black players in the Premier League stopped playing for a day then the league would come to a standstill.”

Yet when it comes to decision-making, from touchlines to boardrooms, the story is different.

In July, Premier League and Football League clubs published workforce diversity data for the first time. Clubs previously collected such data to assist with Equality, Diversity and Inclusion strategies, however under new FA regulations this has now been publicly shared. The Premier League and the EFL say that this will increase transparency and accountability in EDI.

It feels like I’ve had to go backwards to go forwards

Kick It Out’s chief executive, Samuel Okafor, welcomed the publication of the data, when he said: “For many years we have been calling for the game to be more transparent and bring more data into the light.”

“It’s really positive The FA have brought out a new rule that means all 92 clubs have to publish their workforce data.”

However, the group also called for urgency, saying “if we’re still applauding reports instead of reform…we’ve misunderstood the problem.”

Photo by Richard Heathcote/Getty Images

The findings revealed that 78% of club staff across the Premier League are white, that just two clubs in England have Black or ethnic minority coaches in senior roles and that no Black British manager currently works in the top-flight.

As of the 2025/26 season, only one manager of Black or ethnic minority led a Premier League team, Nottingham Forest’s Nuno Espírito Santo a Portuguese manager of Cape Verdean descent.

Espírito Santo was sacked by Forest recently to further underpin xxxxxx

Jason Lee, who played for Forest during the mid-1990s and now champions diversity and inclusion in football with the Professional Footballers Association, said in June that “Nuno is doing great things at Forest and should be celebrated.

“When you see people like him succeed, it makes you think you can be like them too.” His words highlight the importance of visible role models in coaching and management.

Viv Anderson, the first Black player to play for England, has spoken openly about the topic, expressing a strong desire for more “British Black managers to be given opportunities. It’s never materialised and that’s a change we need to see.”

He has also advocated for the introduction of the Rooney Rule stating that “this mustn’t be optional for clubs as otherwise it won’t happen”.

The Rooney Rule is a policy that mandates clubs to interview Black and minority ethnic candidates for managerial roles. Anderson points to figures like Paul Ince and Sol Campbell, whose managerial careers have been plagued by short-term appointments and a lack of sustained support.

Both former England internationals and leaders on the field, Ince and Campbell demonstrated clear potential as coaches but “have not been afforded the opportunities their abilities deserve”.

Darren Moore, now managing at Port Vale, “was not backed and has been harshly sacked numerous times”, according to Anderson.

The highly respected Moore was sacked by West Brom with the club in the Championship play-off places and let go at Sheffield Wednesday following promotion and one of the greatest play-off comebacks in history.

This generation of Black coaches is still hitting a brick wall

Campbell, a former England captain and Champions League veteran, has faced a similar uphill climb. Despite elite credentials, he started his coaching journey at struggling Macclesfield Town and Southend United both clubs riddled with financial and structural issues.

“It feels like I’ve had to go backwards to go forwards,” Campbell once remarked. “The opportunities simply don’t come the same way they do for others.” Despite showing tactical promise, he remains on the managerial sidelines.

Anderson shared a belief that “it may only take a few to make real change”. Whereas, former England international Ricky Hill has said: “This generation of Black coaches is still hitting a brick wall whether it’s access to interviews, mentoring, or security.”

He previously told of how he’s “got three coach of the year awards, won two professional leagues, two in America, one in Trinidad, coached Sheffield Wednesday and Tottenham U19. I feel my body of work is something of reasonable quality. Having said that, I’ve come back with all those accolades, so to speak, but yet still I’m kind of invisible within the UK.”

Like Campbell’s experiences with clubs in trouble, Hill recalls how he “went back as the manager in 2000 (to Luton), took over a club that was in decline at that stage, had been in administration for three-and-a-half years. The soul had been ripped out of the club, but I was given just four months in that post. So that’s the sad part of my journey in that respect.”

Football has long positioned itself as a force for unity, justice, and social progress. From taking the knee to community outreach, the sport knows how to symbolise inclusion. But symbols are not systems. And without structural change, Black excellence may continue to be confined to the pitch.

Until more Black managers like Moore and Campbell are trusted, empowered, and retained English football may remain a space of unfulfilled promise.

Black excellence away from the pitch continues to wait for its opportunity.